Sunday, May 31, 2015

Saturday, May 30, 2015

Paikidze - Krush Analyzed at "Inside Jersey"

Friday, May 29, 2015

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Lissner - Loyd Analyzed at "Inside Jersey"

An 1895 game between Jacob Lissner and Isaac Loyd is analyzed at Inside Jersey.

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Marshall Memorial Day Madness 5/25/2015

On Monday, I finished with a score of 3-2-0 in the tournament at the Marshall Chess Club.

* * * * * * * *

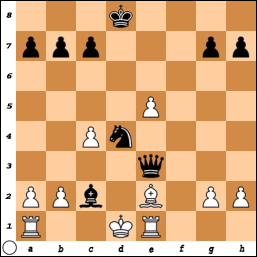

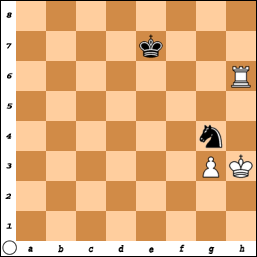

Round One: Philidor Counter Gambit

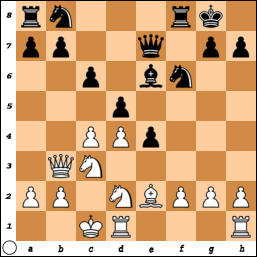

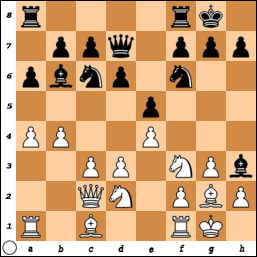

Robert Shibata (USCF 1718) - Jim West (USCF 2221), Marshall Chess Club 5/25/2015

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 f5 4.dxe5 fxe4 5.Ng5 d5 6.c4 Bb4+ 7.Bd2 Qxg5 8.Bxb4 d4 9.Qxd4 Nc6 10.Qd2 e3 11.fxe3 Nxb4 12.Qxb4 Qxe3+ 13.Kd1 Bg4+ 14.Kc2 Bf5+ 15.Kd1 O-O-O+ 16.Nd2 Ne7

17.Be2 Nc6 18.Qc3 Rxd2+ 19.Qxd2 Rd8 20.Qxd8+ Kxd8 21.Rf1 Nd4 22.Re1 Bc2#.

* * * * * * * *

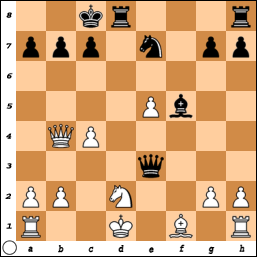

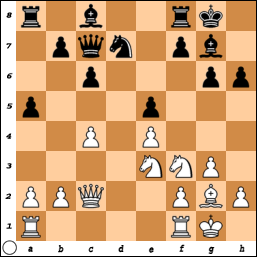

Round Three: Philidor Counter Gambit

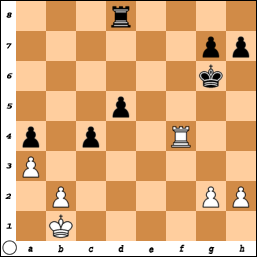

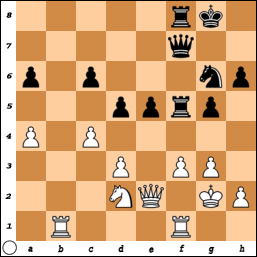

Claudio Mariani (USCF 1930) - Jim West (USCF 2221), Marshall Chess Club 5/25/2015

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 f5 4.dxe5 fxe4 5.Ng5 d5 6.Be3 Be7 7.h4 Bxg5 8.hxg5 Ne7 9.Nc3 Nbc6 10.Bb5 Be6 11.Qd2 a6 12.Bxc6+ Nxc6 13.Bd4 Nxd4 14.Qxd4 c6

15.Qe3 d4 16.Qxe4 dxc3 17.Rxh7 Rxh7 18.Qxh7 Qd2+ 19.Kf1 O-O-O 20.bxc3 Qxg5 21.Re1 Bc4+ 22.Kg1 Re8 23.Qh3+ Be6 24.Re3, White resigns.

Monday, May 25, 2015

Marshall Saturday Game/30 5/23/2015

On Saturday, I finished with a score of 3-0-1 plus a half point bye in the tournament at the Marshall Chess Club.

Round One: Philidor Counter Gambit

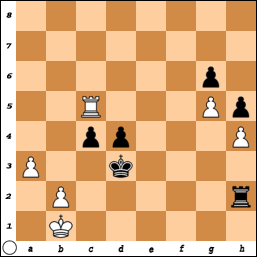

McDermott, Michael (USCF 1800) - Jim West (USCF 2204), Marshall Chess Club 5/23/2015

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 f5 4.Bg5 Be7 5.Bxe7 Qxe7 6.exf5 e4 7.Nfd2 Bxf5 8.Be2 Nf6 9.c4 c6 10.Qb3 d5 11.Nc3 Be6 12.O-O-O O-O

13.f3 a5 14.fxe4 dxe4 15.Ndxe4 Nxe4 16.Nxe4 Na6 17.Bf3 b5 18.d5 bxc4 19.Qc3 cxd5 20.Ng3 Nb4 21.Kb1 Qf6 22.Qxf6 Rxf6 23.Rhe1 Bf7 24.Re7 Rd8 25.Bh5 Bxh5 26.Nxh5 Rf7 27.Rxf7 Kxf7 28.a3 Nd3 29.Rf1+ Kg6 30.Nf4+ Nxf4 31.Rxf4 a4

32.Kc2 d4 33.Kd2 Rd5 34.Re4 Kf7 35.g4 h6 36.h4 g6 37.Rf4+ Ke6 38.Re4+ Kd6 39.Rf4 Ke5 40.Rf8 Rb5 41.Kc2 Rb3 42.Ra8 Rg3 43.Rxa4 Rg2+ 44.Kc1 Kd5 45.Ra5+ Ke4 46.g5 Kd3 47.Kb1 h5 48.Re5 Re2 49.Rc5 Rh2

50.Rc6 Rxh4 51.Rxg6 Rh1+ 52.Ka2 Kc2 53.Rf6 d3 54.Rf2+ d2 55.Rg2 Kc1, White resigns.

Sunday, May 24, 2015

Chess Program on Upper West Side

[photo by Kevin Hagen]

By RALPH GARDNER JR.

May 20, 2015 8:15 p.m. ET

Zachary Targoff is a better man than I am. I doubt I’d have used all my bar mitzvah money to do what Zach did with his nest egg.

He started a chess program a year ago in April at Dorot, a Jewish social services organization on the Upper West Side that works to make older adults less socially isolated. To that end, and with the support of Zach and his parents, Dorot brings together teenagers and seniors to play chess.

“We used the money I got from my bar mitzvah to fund this program,” the 14-year-old Zach said as he looked around the room where the young and old were hunched over chess boards. His donation paid for staff, refreshments, transportation for the seniors, and chess equipment and training.

“I’m thrilled you’re teaching me chess,” Florence Chasen, 97, told the teenager as she moved her knight two spaces rather than the customary three.

“The knight goes two spaces and then one space,” Zach explained patiently.

A more dangerous opponent was 91-year-old Herman Bomze, who was engaged in a match on the other side of the room and who helped inspire the program. Zach and Mr. Bomze have been playing against each other since before Zach’s bar mitzvah in November 2013.

“I was nervous the first time,” Zach recalled of his formidable opponent. “I expected we’d talk for five minutes about normal things. I knew once we started playing that the game would speak for itself.”

So who wins?

“When I first started playing with him, we would be splitting games,” said Zach, an eighth-grader at the Trinity School. “I thought I’d have to be giving up games.

“As people get older things happen,” he added, choosing his words carefully. “He’ll still win games.”

The players meet weekly during the school year. The timing is different during the summer, explained Judith Turner, Dorot’s director of volunteer services.

“Teens go to seniors’ homes and bring the chessboard with them,” Ms. Turner said. “We were so amazed by the outpouring of interest.”

Zach and Mr. Bomze ended up talking about more than chess. The nonagenarian shared some of his personal history with the boy.

“He told me a lot about his family,” Zach said. “How they came over from Europe. He showed me pictures of his family.”

And as a bar mitzvah gift, Mr. Bomze gave Zach the chess set his father, who didn’t survive the Holocaust, had given him.

“Unfortunately, his father couldn’t get a visa to America,” Zach explained as Ms. Chasen moved one of her pawns straight ahead—a move that would be acceptable in checkers but not in chess. “He was forced to stay in Europe and killed during the war.”

“Remember the pawns capture diagonally,” Zach reminded her.

I thought it best to let Ms. Chasen and Zach finish their game without further interruption and made my way to Mr. Bomze, who was in a spirited contest with 13-year-old Mason Sklar, a student at Hunter College High School.

“Technically I’m winning,” Mason explained. “But I’m in a bad situation.”

Since Mr. Bomze apparently had his hands full, his daughter, Bracha Nechama Bomze, a poet who accompanied him to the program, shared a bit of her father’s story.

“He fled the Nazis in 1939,” she said. “He was 15. But his father was deported to Buchenwald.”

Ms. Bomze said her dad had learned to play chess when he was 6, on the set he gave Zach. By the time he was 8, he was beating his father.

“I said, ‘Why not use this set, Dad?’ ” Ms. Bomze recalled of Zach’s visits to their home. He wouldn’t “because it was so emotionally laden.”

There were discussions about whether to give the set to Zach as a bar mitzvah gift. It could just as easily have gone to a member of the younger generation of Mr. Bomze’s family.

“He was touching it with such sensitivity,” Ms. Bomze recalled of Zach and the hand-carved pieces. “Caressing it actually. Herman and his sister agreed Zach would be the most appropriate recipient of this precious heirloom.”

Ms. Bomze tried to ask her father a question regarding the chess set. “I’m in the middle of chess,” he told her.

He was simultaneously eating a piece of cake.

I should mention this was the last session of the school year; to celebrate the occasion, a chess-themed cake was rolled out. Between the cake and the chess, Mr. Bomze had little bandwidth for extraneous conversation with his daughter or with me.

“It takes precedence, I guess,” his daughter said.

She went on to explain that her father, a retired structural engineer —“I still am a structural engineer,” he stated briefly, correcting us—had suffered a near fatal heart attack in December.

“So this whole relationship is amazing,” she said of the program in general and her father’s relationship with Zach, in particular. “When he’s playing chess, he’s at his best.”

“He won,” Mason announced.

“It was a big struggle, though,” Mr. Bomze admitted.

Zach dropped by after his game, or more accurately after the free lesson he gave to Ms. Chasen.

“Do you want to play?” he asked Mr. Bomze.

The question wasn’t a difficult one: “I’ll play again,” Mr. Bomze said.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Friday, May 22, 2015

Chess Class at Hudson Montessori School

For the next two Wednesday afternoons, I will be the substitute teacher for the chess class, conducted by 101 Discoveries, at the Hudson Montessori School in Jersey City.

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Fries-Nielsen - Carstensen at "Inside Jersey"

A new move 6.Qd2 against the Sicilian Najdorf, from a game between IM Jens Ove Fries-Nielsen [pictured, top left] and IM Jacob Carstensen [pictured, bottom right], is analyzed at Inside Jersey.

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

Ultimate War Game: Bridge (Not Chess)

[photo by Getty Images]

According to this article in the Wall Street Journal, the ultimate war game is (chess) bridge.

By MICHAEL LEDEEN May 17, 2015 5:54 p.m. ET

On the night of Nov. 7, 1942, as allied forces in Operation Torch headed for the North African coast, commanding Gen. Dwight Eisenhower waited anxiously. It was foggy, and news of the invasion was slow to arrive. To pass the time, Ike and three associates played bridge.

The game was an important part of Ike’s life—throughout the war, in the White House and in retirement. In those years many American leaders were passionate bridge players: One of the men at Eisenhower’s table that night was Gen. Alfred Gruenther, later NATO Commander and for many years president of the World Bridge Federation. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles bragged about his mastery of the game, and his department long conducted a world-wide bridge tournament in embassies and consulates.

You’ll often hear that chess is the ultimate model for geopolitics, indeed for war itself. In the 1963 hit movie “From Russia With Love,” James Bond is menaced by the brilliant Soviet chess master Tov Kronsteen (clearly modeled on Boris Spassky).

But Eisenhower knew better. No board game can replicate the conditions of the battlefield or the maneuvers of geostrategy, for one simple reason: All of the pieces are visible on the table. Card games are better models because vital information is always concealed by the “fog of war” and the deception of opponents. Most of the time a bridge player sees only one-quarter of the cards, and some of the information he might gather from them is false.

Bridge is largely about communication, and every message a player sends—by bidding or playing a significant card—is broadcast to the player’s partner and his opponents. Frequently a player will have to decide whether he would rather tell the truth to his partner (thereby informing his opponents) or deceive the enemy (thus running the risk of seriously fooling his ally across the table).

Nothing like this exists in even the greatest board games. They permit some feints, to be sure, but not outright lies. Great bridge players are great liars—as are brilliant military leaders and diplomats and politicians. To take the most celebrated recent example, Deng Xiaoping, the man who transformed modern China, was an avid bridge player who had a private railroad car for his games.

The difficulty of weighing truth and lies is one reason that computers don’t win at bridge, whereas at the highest level of chess they do very well. IBM’s Deep Blue defeated grandmaster Garry Kasparov in a six-game match in 1997, but bridge is simply too tough for the machines.

Bridge may also be too tough for contemporary Americans. The bridge-playing population is shrinking and aging. In Eisenhower’s time, close to half of American families had at least one active bridge player; as of 10 years ago, a mere three million played at least once a week, and their average age was 51. Kibitz at a national bridge championship or a local club game and you’ll be impressed by the white hair and the number of wheel chairs and oxygen tanks.

Another measure: When Operation Torch landed, there were several bridge books on the best-seller list. Nowadays bridge books are printed in small numbers by specialized publishers. Poker books do somewhat better, but no writer’s celebrity approaches that of Ely Culbertson or Charles Goren, the high-profile bridge authors in the past century.

The shrinking population of American bridge players goes hand in hand with other evidence of declining mental discipline, including shortening attention spans and decreases in book readership. You can’t be a winning card player unless you can concentrate for several hours, and mastery of the game takes years. Neither is bridge a solo activity; you need a partner with whom you must reach very detailed agreements about myriad situations. All this is good for the mind: Bridge provides stimulation that can help players retain their mental toughness and stave off dementia.

Eisenhower and Gruenther would be disturbed by the declining popularity of bridge, knowing that it is a quintessential American game, developed in its modern form in the 1920s largely on board the Vagrant, Harold Vanderbilt’s yacht. American players continue to win in international competition, but they are mostly professionals. Insofar as they have day jobs, they are often stock or options traders, not business leaders, diplomats or military officers.

It might be helpful to introduce bridge instruction and competition to high schools and colleges, as has been done with chess. Bridge lovers like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett would surely approve and could sponsor programs and tournaments for young players, with suitable rewards.

It’s no accident that the greatest thinker of modern times, Niccolò Machiavelli, was a card player, nor that his masterpiece, “The Prince,” remains essential reading for our special forces officers. A prince, Machiavelli wrote, should be “faithful to his word, guileless” but “his disposition should be such that, if he needs to be the opposite, he knows how.” That’s a lesson you can only learn from kings and jacks, not kings and rooks.

Mr. Ledeen, a freedom scholar at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, is a bridge life master and the former coach of the Israeli national bridge team.

According to this article in the Wall Street Journal, the ultimate war game is (

By MICHAEL LEDEEN May 17, 2015 5:54 p.m. ET

On the night of Nov. 7, 1942, as allied forces in Operation Torch headed for the North African coast, commanding Gen. Dwight Eisenhower waited anxiously. It was foggy, and news of the invasion was slow to arrive. To pass the time, Ike and three associates played bridge.

The game was an important part of Ike’s life—throughout the war, in the White House and in retirement. In those years many American leaders were passionate bridge players: One of the men at Eisenhower’s table that night was Gen. Alfred Gruenther, later NATO Commander and for many years president of the World Bridge Federation. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles bragged about his mastery of the game, and his department long conducted a world-wide bridge tournament in embassies and consulates.

You’ll often hear that chess is the ultimate model for geopolitics, indeed for war itself. In the 1963 hit movie “From Russia With Love,” James Bond is menaced by the brilliant Soviet chess master Tov Kronsteen (clearly modeled on Boris Spassky).

But Eisenhower knew better. No board game can replicate the conditions of the battlefield or the maneuvers of geostrategy, for one simple reason: All of the pieces are visible on the table. Card games are better models because vital information is always concealed by the “fog of war” and the deception of opponents. Most of the time a bridge player sees only one-quarter of the cards, and some of the information he might gather from them is false.

Bridge is largely about communication, and every message a player sends—by bidding or playing a significant card—is broadcast to the player’s partner and his opponents. Frequently a player will have to decide whether he would rather tell the truth to his partner (thereby informing his opponents) or deceive the enemy (thus running the risk of seriously fooling his ally across the table).

Nothing like this exists in even the greatest board games. They permit some feints, to be sure, but not outright lies. Great bridge players are great liars—as are brilliant military leaders and diplomats and politicians. To take the most celebrated recent example, Deng Xiaoping, the man who transformed modern China, was an avid bridge player who had a private railroad car for his games.

The difficulty of weighing truth and lies is one reason that computers don’t win at bridge, whereas at the highest level of chess they do very well. IBM’s Deep Blue defeated grandmaster Garry Kasparov in a six-game match in 1997, but bridge is simply too tough for the machines.

Bridge may also be too tough for contemporary Americans. The bridge-playing population is shrinking and aging. In Eisenhower’s time, close to half of American families had at least one active bridge player; as of 10 years ago, a mere three million played at least once a week, and their average age was 51. Kibitz at a national bridge championship or a local club game and you’ll be impressed by the white hair and the number of wheel chairs and oxygen tanks.

Another measure: When Operation Torch landed, there were several bridge books on the best-seller list. Nowadays bridge books are printed in small numbers by specialized publishers. Poker books do somewhat better, but no writer’s celebrity approaches that of Ely Culbertson or Charles Goren, the high-profile bridge authors in the past century.

The shrinking population of American bridge players goes hand in hand with other evidence of declining mental discipline, including shortening attention spans and decreases in book readership. You can’t be a winning card player unless you can concentrate for several hours, and mastery of the game takes years. Neither is bridge a solo activity; you need a partner with whom you must reach very detailed agreements about myriad situations. All this is good for the mind: Bridge provides stimulation that can help players retain their mental toughness and stave off dementia.

Eisenhower and Gruenther would be disturbed by the declining popularity of bridge, knowing that it is a quintessential American game, developed in its modern form in the 1920s largely on board the Vagrant, Harold Vanderbilt’s yacht. American players continue to win in international competition, but they are mostly professionals. Insofar as they have day jobs, they are often stock or options traders, not business leaders, diplomats or military officers.

It might be helpful to introduce bridge instruction and competition to high schools and colleges, as has been done with chess. Bridge lovers like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett would surely approve and could sponsor programs and tournaments for young players, with suitable rewards.

It’s no accident that the greatest thinker of modern times, Niccolò Machiavelli, was a card player, nor that his masterpiece, “The Prince,” remains essential reading for our special forces officers. A prince, Machiavelli wrote, should be “faithful to his word, guileless” but “his disposition should be such that, if he needs to be the opposite, he knows how.” That’s a lesson you can only learn from kings and jacks, not kings and rooks.

Mr. Ledeen, a freedom scholar at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, is a bridge life master and the former coach of the Israeli national bridge team.

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Marshall May Under 2300 5/17/2015

On Sunday, I drew this game in the tournament at the Marshall Chess Club.

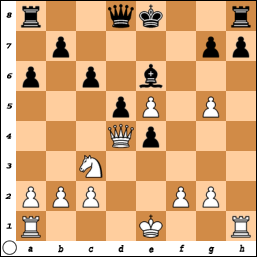

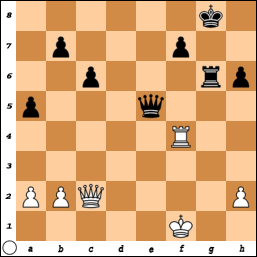

Round Four: King's Indian Attack

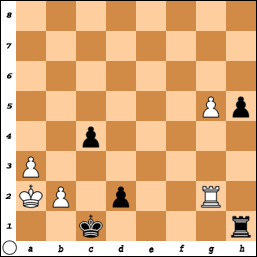

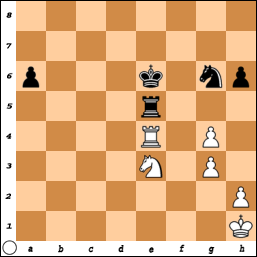

Jim West (USCF 2206) - Wesley Wang (USCF 2113), Marshall Chess Club 5/17/2015

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.g3 Nf6 4.d3 Bc5 5.Bg2 O-O 6.O-O d6 7.Nbd2 Be6 8.c3 a6 9.a4 Qd7 10.b4 Bb6 11.Qc2 Bh3

12.Nc4 Bxg2 13.Kxg2 h6 14.Be3 Bxe3 15.Nxe3 Ne7 16.Nh4 Ng4 17.Qe2 Nxe3 18.Qxe3 g5 19.Nf3 Qc6 20.c4 f5 21.b5 Qe8 22.exf5 Rxf5 23.Qe4 Qf7 24.Nd2 Rf8 25.f3 c6 26.bxa6 bxa6 27.Rab1 d5 28.Qe2 Ng6

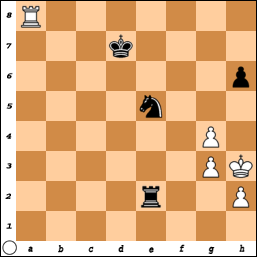

29.Kh1 g4 30.fxg4 Rf2 31.Rxf2 Qxf2 32.Qxf2 Rxf2 33.Rd1 Re2 34.cxd5 cxd5 35.a5 Kf7 36.Nb3 e4 37.Nd4 Ra2 38.dxe4 dxe4 39.Rf1+ Ke7 40.Re1 Kd6 41.Nf5+ Kd5 42.Rd1+ Ke5 43.Ne3 Ke6 44.Rd4 Rxa5 45.Rxe4+ Re5

46.Ra4 Rxe3 47.Rxa6+ Kf7 48.Kg2 Re2+ 49.Kh3 Kg7 50.Ra7+ Kf6 51.Ra1 Ne5 52.Rf1+ Kg6 53.Rf4 Nf7 54.Rf5 Kg7 55.Ra5 Ne5 56.Ra7+ Kf8 57.Ra6 Kg7 58.Ra7+ Kg8 59.Ra8+ Kf7 60.Ra7+ Ke8 61.Ra8+ Kd7

62.Ra7+ Kc8 63.Ra8+ Kb7 64.Rf8 Kc6 65.Rf5 Kd6 66.Rf6+ Ke7 67.Rxh6 Rxh2+ 68.Kxh2 Nxg4+ 69.Kh3, draw.

Monday, May 18, 2015

Marshall May Under 2300 5/16/2015

On Saturday, I won this game in the tournament at the Marshall Chess Club.

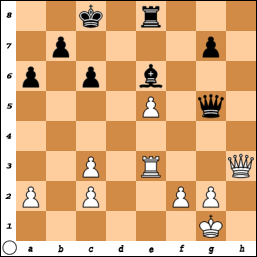

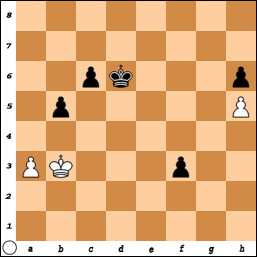

Round Three: King's Indian Defense, Fianchetto Variation

Lawrence Dirks (USCF 1640) - Jim West (USCF 2206), Marshall Chess Club 5/16/2015

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 g6 3.g3 Bg7 4.Bg2 O-O 5.c4 d6 6.O-O Nbd7 7.Nc3 e5 8.Bg5 h6 9.Bxf6 Bxf6 10.Nd5 Bg7 11.dxe5 dxe5 12.e4 c6 13.Ne3 Qc7 14.Qc2 a5

15.c5 Re8 16.Rad1 Bf8 17.Bh3 Nxc5 18.Ng4 Bxg4 19.Bxg4 Rad8 20.Rd2 Rxd2 21.Nxd2 Ne6 22.Bxe6 Rxe6 23.f4 exf4 24.gxf4 Bg7 25.e5 g5 26.Nc4 gxf4 27.Rxf4 Rg6+ 28.Kf1 Bxe5 29.Nxe5 Qxe5

30.Qe4 Qxe4 31.Rxe4 Rf6+ 32.Ke2 Re6 33.Ke3 Rxe4+ 34.Kxe4 f6 35.a3 Kf7 36.h4 Ke6 37.h5 a4 38.Kf4 b5 39.Ke4 f5+ 40.Kd4 Kd6 41.b4 axb3 42.Kc3 f4 43.Kxb3 f3, White resigns.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)