Think Cheating in Baseball Is Bad? Try Chess

Smartphones, buzzers, even yogurt — chess has nearly seen it all in both live and online tournaments. And just as in baseball, technology only makes it harder to root out.

By

David Waldstein

Published March 15, 2020

Updated March 16, 2020

Until the sports world ground to a halt last week over the coronavirus outbreak, perhaps the biggest issue looming over professional sports in the United States was the Houston Astros’ cheating scandal. The revelations of their scheme led Major League Baseball’s commissioner, Rob Manfred, to deliver a stern warning to all 30 club owners that there was a “culture of cheating” in the game.

But baseball’s malfeasance — sign-stealing or otherwise — has nothing on chess. At prestigious live tournaments and among thousands of others playing daily online, cheating is a scourge.

Whether it’s a secret buzzer planted in a shoe, a smartphone smuggled into the bathroom, a particular flavor of yogurt delivered at a key moment — or just online players using computerized chess programs — chess has perhaps more cheating than any other game in the world.

“Of course it is a problem,” said Leinier Domínguez, the Cuban-born player currently ranked No. 3 in the United States. “Because with all the advances in technology, it’s always a possibility. People have more chances and opportunities to do this sort of thing.”

In both chess and baseball, both real and rumored instances of cheating have been around for decades, but an explosion in technology and data over the past 10 to 15 years has made the problem much harder to curb for both.

The Astros’ scheme, which helped propel them to the 2017 World Series title, involved illegally deciphering the signs of opposing catchers via a live video feed and then banging on a trash can to signal the next pitch to the batter. M.L.B. is now grappling with how to prevent similar electronic-based schemes in the future.

In chess, players at live tournaments are now required to leave their phones behind and pass through metal detectors before entering the playing area. Some have even been asked to remove clothing and been searched. And some tournaments now put players behind one-way mirrors to limit visual communication.

But, like the Astros, many chess players still try.

Just last year, a grandmaster named Igors Rausis was caught examining a smartphone in a bathroom stall at a tournament in France. In 2015, Gaioz Nigalidze of Georgia was barred for three years by FIDE, chess’s global governing body, and had his grandmaster status revoked for the same offense.

FIDE’s anti-cheating commission has recently stepped up its efforts to combat the problem. The group met last month and resolved to give financial support to national federations that need it to help them root out cheating, and will share detection techniques with online chess platforms. They are currently investigating 20 cases.

“The cheaters have been winning for a long time,” Arkady Dvorkovich, the president of FIDE, said in a telephone interview from Moscow. “But in the last few months we showed our determination to fight it and I think people realize it is serious.”

In 2013, Borislav Ivanov, a young player from Bulgaria, was essentially forced into retirement after he refused to take off his shoes to be searched for an electronic device that might be used to transmit signals to him. A device was never found — Ivanov reportedly refused to remove his shoes because, he claimed, his socks were too smelly — but he retired shortly after the tournament.

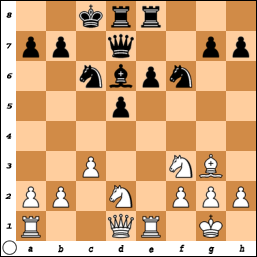

Dominguez said he did not think the top 20 players in the world cheat: It would be too risky to their reputations, he said. But he was at the 2012 chess Olympiad in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia, when accusations flew that the French team had used an elaborate cheating scheme. The French team was accused of sending text messages to teammates, who would then stand in prearranged spots in the gallery. Their location was supposedly the signal to a young, unproven player, Sébastien Feller, for the next move.

Feller denied the accusations but was suspended by the French chess federation, which said it discovered numerous suspicious texts. That penalty was later overruled by a French court.

Dominguez was not playing Feller, but saw the furor at the time and its effects even on clean players.

“One of the dangers is that you get a bit paranoid about these things,” Dominguez said. “Maybe in baseball as well. You feel insecure and lose focus on your game.”

There are players who cheat by sandbagging — intentionally playing poorly in order to qualify for a lower tournament and win the prize money. There are some who create fake accounts online, build up the stature of that account, and then beat it in order to improve their own ranking. Sometimes opponents agree to an outcome and share meager prize money.

In 1978, Viktor Korchnoi accused Anatoly Karpov of cheating with blueberry yogurt. After Karpov received purple yogurt from a waiter during the game, Korchnoi worried that the flavor was a signal from someone on the outside.

Korchnoi later claimed his accusation was a joke, but officials took it seriously, ultimately mandating that the same snack would be delivered to both players at a predetermined time.

“It sounds crazy,” said Gerard Le-Marechal, a full-time monitor and anti-cheating detective for Chess.com, one of the world’s largest online chess platforms. “But it’s a legitimate concern because there are so many ways to help a player.”

Le-Marechal is one of six people employed by the website to combat cheating. They rely on sophisticated algorithms of statistical data, and Le-Marechal says he gets ping alerts throughout the day about cheaters — many amateurs, some professionals and even the occasional grandmaster.

During a 40-minute telephone interview, at least three pings could be heard in the background, and Le-Marechal said all were alerts for cheating.

Daniel Rensch, a former junior champion and one of the owners of Chess.com, said his cheat-detection team had consulted for live tournaments to help stop cheating. There is little doubt, he said, that haptic buzzers have already been used.

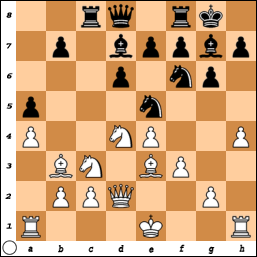

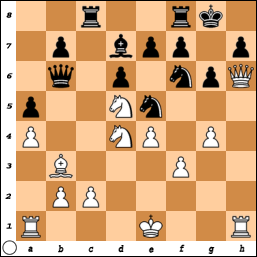

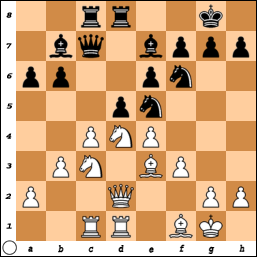

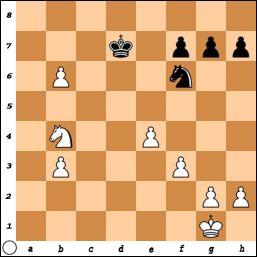

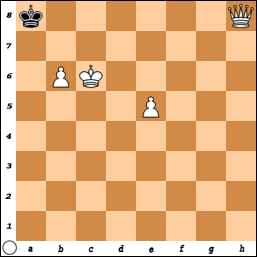

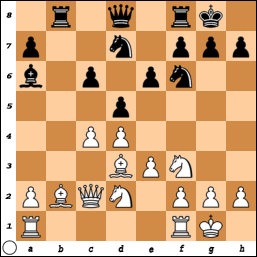

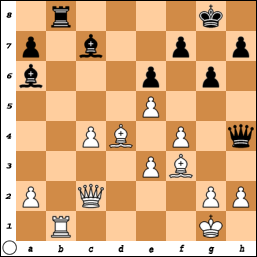

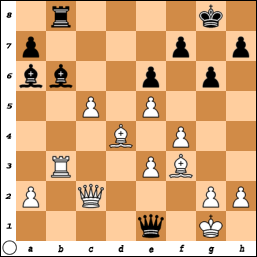

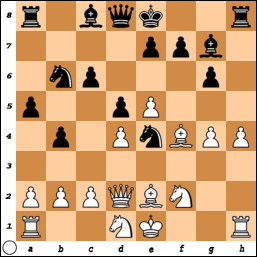

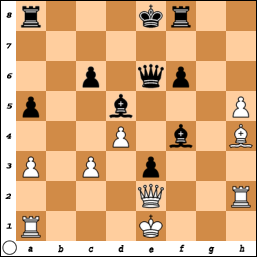

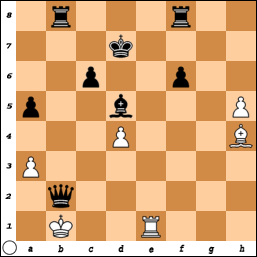

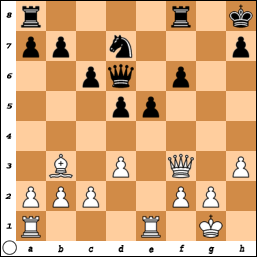

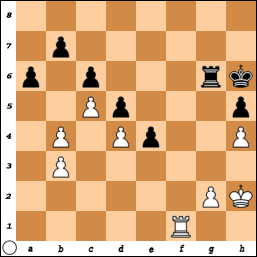

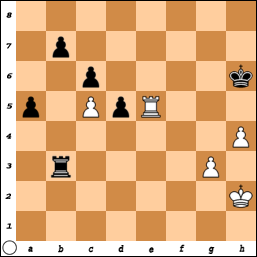

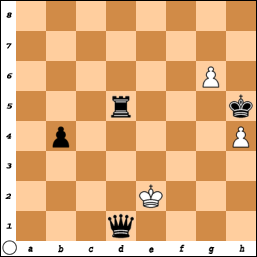

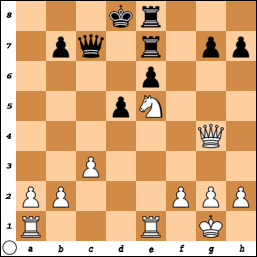

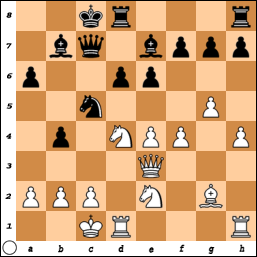

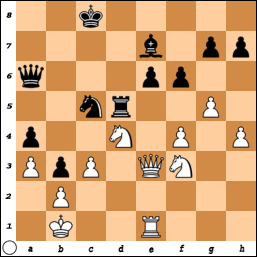

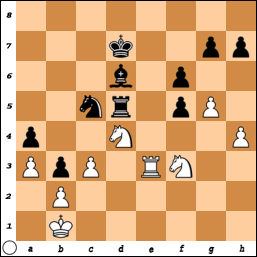

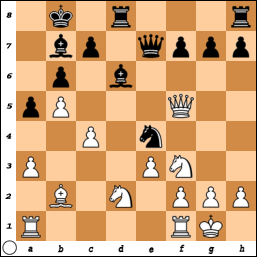

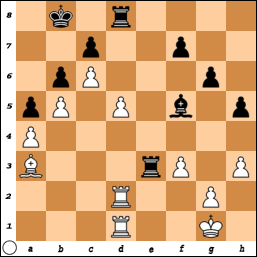

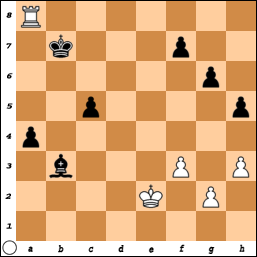

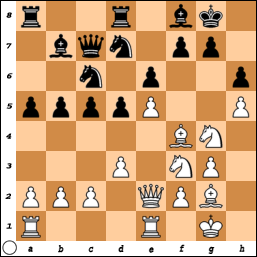

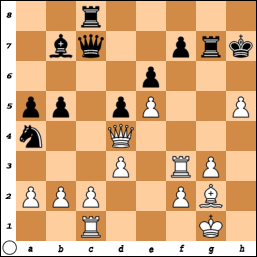

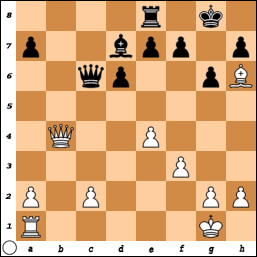

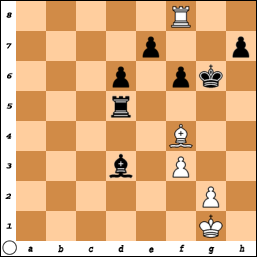

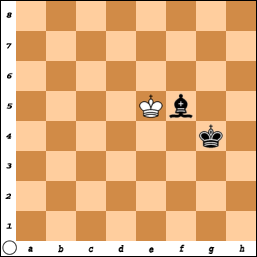

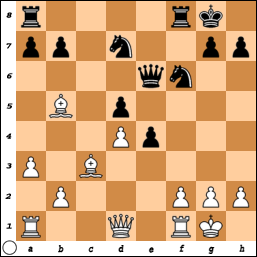

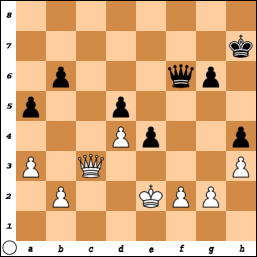

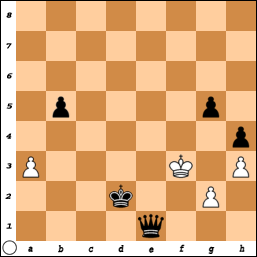

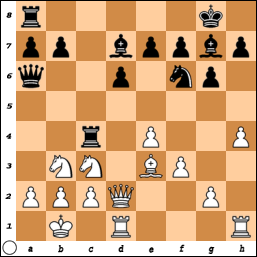

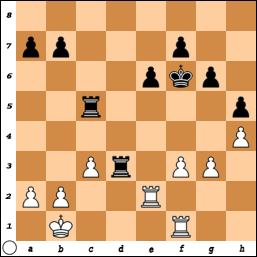

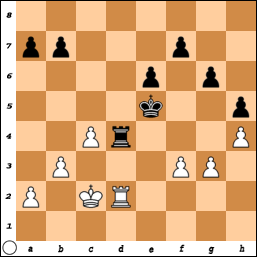

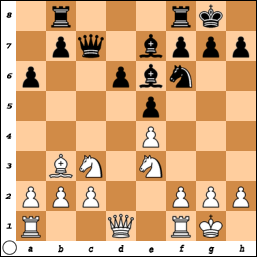

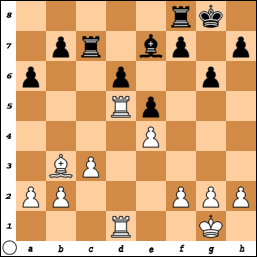

The idea is that, while one person plays, another watches from a remote location and simultaneously pores over potential moves on a computerized chess engine. Then the accomplice would signal the best upcoming moves to the player via the haptic device that taps (or buzzes) a coded signal for the player.

A top player does not necessarily need to be told the exact move. In some cases, the prearranged signal could simply be: There is a winning move here. Grandmasters are skilled enough to find it.

Buzzers have also fueled plenty of speculation in the Astros scandal. Though they were found only to have cheated in the 2017 season, many suspected they continued beyond then — in part because of a video that showed second baseman Jose Altuve telling teammates not to rip off his shirt after hitting a home run during the 2019 postseason.

Altuve and the Astros denied the accusations, but it has done little to quell rumors and questions: Could baseball players effectively use haptic devices?

“One hundred percent,” Rensch said, “and it would not even be that complicated.”

During his team’s investigations, Rensch said, a knowledgeable source indicated that tiny electronic earpiece receivers, the size of a peppercorn, were being used to cheat in chess. The insidious miniature earbuds, which are marketed online to students for the expressed purpose of cheating on exams, are so small that they cannot be detected.

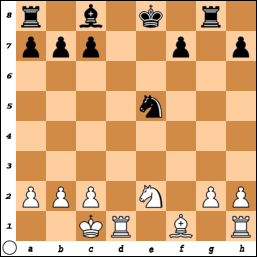

But Rensch is more concerned with the scourge of online cheating on his platform. Ever since the IBM computer Deep Blue beat the world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, increasingly powerful chess engines have made cheating easy.

“It’s so much worse now,” Le-Marechal said. “You have this almighty god that can tell you everything. It’s so tempting for everybody.”

About 10 years ago, as rank amateurs were beating grandmasters and rampant cheating threatened the legitimacy of online chess, Rensch and his fellow owners of the site held a meeting on the topic. At that point they were hosting a million games a day — now it is 3.5 million — and someone suggested there might be nothing they could do to stem the rolling tide of deception.

“Just saying it out loud was enough to make us kind of vomit in the back of our throats,” Rensch said. “We were like, ‘No, we have to do something.’ We have a responsibility as a steward of the game to try to solve this problem, that everybody and their cousin with a free freaking program was suddenly the best chess player in the world.”

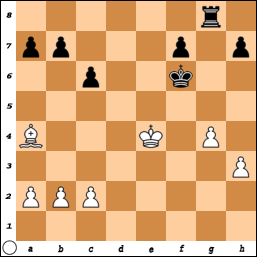

The website also hosts tournaments for money, making cheat-detection even more critical. So the team developed computer programs that mine statistical data to prove cheating, which they say has saved the online game. They often do not even know how someone is cheating, but they can prove it is happening based on irregularities in the moves over time.

Rensch said they shut down sometimes tens of thousands of accounts a month, including some of professionals and grandmasters.

They can also spot irregularities in live matches. According to Le-Marechal, they knew about Rausis months before he was busted in the bathroom in France last year. Even some professionals — whom Rensch’s team does not name publicly — have confessed, apologized and wondered how they were caught.

“I don’t care how you are doing it,” Rensch said. “All I’m saying is, what you are doing is not reasonably possible based on the data I have, and I would win in court.”

Rensch and Le-Marechal believe that other sports, particularly baseball with its wide use of statistical data, can adopt their approach to catching cheaters. Dvorkovich, the head of FIDE, added that just as the cheaters benefit from technology, the authorities can, too.

“No matter what the game is,” Dvorkovich said, “when there are benefits from winning, you have cheating.”